He is how he is because society says he is a vile, twisted creature

(Rob James-Collier, 2014)

He’s plotted with sideburns O’Brien to get Bates fired, got himself a ‘Blighty’ to decamp from the ravages of the First World War, has been blackmailing the gritted back teeth off of Baxter over her pilfering secret, and his favourite past time is to manipulate people from all floors of the resplendent Downton Abbey for his own amusement. Yet the queer under-butler Thomas Barrow of recent episodes is not quite the same character that Julian Fellows originally penned back in 2010. Although his sexuality was made clear with a ‘controversial’ kiss in the first episode, Barrow’s queerness was almost entirely absent from the second series of the award-winning programme, and has somewhat wavered ever since. Actor Rob James-Collier was so concerned about this omission that he was compelled to ask Fellows if his character was ‘still gay’. Twitter authors have shown their disdain for the inconsistencies within his characterisation, and have bemoaned the villainous streak that runs throughout Downton’s queers. One contributor complained that ‘it wasn’t enough that the principle gay had to be bad’, but that ‘all the others are too’, whereas Vanity Fair columnist Richard Lawson wrote ‘Complaint about #DowntonAbbey: Why must the gay guy be the villain?’. Audiences were promised that a ‘romance’ would further colour Barrow’s sexuality in series three, and yet it was an unrequited love that allowed audiences to see the softer, more generous Thomas, who took a beating for Jimmy, the object of his desire.

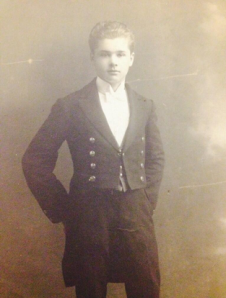

With the last series of Downton Abbey now airing, I have taken some time to consider why domestic service dramas fascinate me and so many of us so much. When I’m not writing and researching, I generally watch a shed load of old telly that in turn makes me research and write some more. Of late I’ve been revisiting The Duchess of Duke Street and Upstairs Downstairs after conducting a series of oral interviews with my Nan about her life, and digging through the family archive that she has. My family have lived on Lord Sheffield’s Estate in East Sussex for over seven generations, and the vast majority of my ancestors who were in his service are remembered in these dusty, fascinating boxes. Considering that by the late nineteenth century, domestic service provided the majority of employment for women in Britain, it is probable that domestic service has featured, at some point, within a great number of our family trees. Beyond the allurement of corsets and candelabras upstairs, these widespread familial connections to histories from below can help us to understand why domestic service remains such an attraction in popular culture. As Alison Light suggests, domestic service remains deep in our ‘collective psyche’; it has the power to conjure ideas of deference, belligerence, resentment and envy for a way of life that seemingly no longer exists.

With the last series of Downton Abbey now airing, I have taken some time to consider why domestic service dramas fascinate me and so many of us so much. When I’m not writing and researching, I generally watch a shed load of old telly that in turn makes me research and write some more. Of late I’ve been revisiting The Duchess of Duke Street and Upstairs Downstairs after conducting a series of oral interviews with my Nan about her life, and digging through the family archive that she has. My family have lived on Lord Sheffield’s Estate in East Sussex for over seven generations, and the vast majority of my ancestors who were in his service are remembered in these dusty, fascinating boxes. Considering that by the late nineteenth century, domestic service provided the majority of employment for women in Britain, it is probable that domestic service has featured, at some point, within a great number of our family trees. Beyond the allurement of corsets and candelabras upstairs, these widespread familial connections to histories from below can help us to understand why domestic service remains such an attraction in popular culture. As Alison Light suggests, domestic service remains deep in our ‘collective psyche’; it has the power to conjure ideas of deference, belligerence, resentment and envy for a way of life that seemingly no longer exists.

Sheffield Park House (Left) and plans for the Carpenters Cottage on the Sheffield Park Estate (1891 – Right)

We still use great-great-Grandma’s Christmas Pudding recipe that she served as Cook at ‘the big house’, and steam engines still thunder down the railway line that Lord Sheffield privately sponsored. At times, these remnants of the aristocratic governance of where I live seems to have the power to provide a sensory connection to the past. My childhood was filled with stories of ‘Upstairs Downstairs’ tales from much-loved Great Aunts who were all domestic servants. Like so many historians, these stories have not only shaped my cultural interests but also the subjects which I choose to research. I spent hours watching videos of Upstairs Downstairs and The Duchess of Duke Street with them, and can’t help but shed tears when I do so now that they are long gone. Domestic service has been the source of countless historical films and television dramas; recreating what was undeniably the scaffolding of British social life throughout the twentieth century. Almost all of these domestic service dramas feature queer characters within their narratives, and almost all of them are portrayed in a similarly negative light.

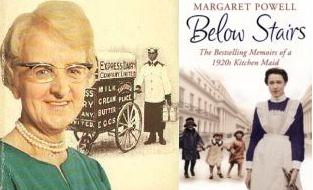

In 1968, Margaret Powell’s autobiographical work Below Stairs was published, selling 14,000 copies in its first year. Within her many recollections of her ten years in domestic service is a rare glimpse into homosexual life in service in the 1920’s. We are introduced to the valet in her place of work in an interwoven narrative in which she also discusses marriage. The valet’s character forms the antithesis of her own bread-winning marital ambition. His age, ‘…about forty five’, is of utmost concern to her, indicating that she believed that he should have risen further within the social structure of the household than he had. We can understand from her narrative that his sexuality prevents his ascendancy to under-butler because of his lack of masculinity. Her depiction of him is an anatomy of his very being; her confusion over his identity is shaped against her biological understandings of masculinity:

… His hands were so soft, and he was so soft spoken, he didn’t seem masculine. More like a jelly somehow, to me. I assume of course that he could sire children. I presume he was all there, organically speaking.

Although it is clear that Powell both disliked and disproved of the valet, she suggests that her own repulsion was not shared by the rest of the household staff, stating that the cook ‘made a fuss of him’ and that ‘everyone spoke and laughed with him’.

Margaret Powell

Powell’s memoir has been credited for inspiring many of the dramatised depictions of domestic service on television and films, which have often included the 1920’s (in which she served) as well as other earlier time periods, and featuring ‘grander’ houses than those Powell had worked in. Many of the characters that feature in these films are moulded from her memories, most frequently the homosexual valet. Yet it seems that we are repeatedly given characters that Powell herself would have approved of – nasty, scheming and crucially unusual outsiders – and not the sociable and well-liked queer character that Powell resented. Little has been written about the lives of queer domestic servants. This is largely due to the fact that almost no autobiographical or life history material exists which illuminates the narratives of those who worked in this field of employment. We do know that in 1924, 24% of those who were arrested for homosexual offences were employed in domestic service, and that later, in 1954, when live-in domestic service was in serious decline, the figure was 10%. As Matt Cook states in his work on Queer Domesticities, for some queer servants, ‘living in’ provided an opportunity to find sex, relationships, some camaraderie, and a means of living away from possibly restrictive family homes. Living on site, though, often also meant compromised privacy and a double insecurity: both job and home could be lost if they were found out. Though in domestic roles, these men had paradoxically often not had a home of their own- or at least not the kind that was being idealised more broadly.

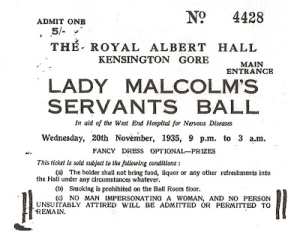

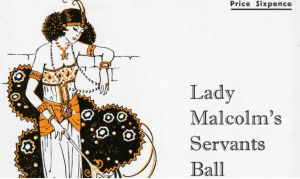

Perhaps our most vivid and colourful insight into queer life in service can be found in the many servants’ balls that Lady Jeanne Malcom held between 1923 and 1938. Originally established to provide a social event for domestic servants, it rapidly became a site of queer expression. Matt Houlbrook’s beautiful research in Queer London suggests that these events:

…embodied competing understandings of sexual difference and the unstable boundaries between difference and “normality” in the first half of the twentieth century. (p.269-270)

Houlbrook’s work demonstrates how

hundreds of working-class queans flocked to the balls, discarding the masks they wore in everyday life, wearing drag, dressing outrageously, and socialising unashamedly while never appearing to be anything out of the ordinary. (p.267)

By 1935, tickets to Lady Malcolm’s Ball were issued with a warning that ““No Man Impersonating a Woman …… will be admitted or permitted to remain”

By 1935, however, the tickets were marked with warnings against cross-dressing, and Lady Malcolm retained staff to eject any ‘undesirables, and their names are listed in police records and in newspaper exposes. Beyond the fancy dress, the lipstick, the laughter in the darkness remained criminality. Culture seems to have hung on to the criminality of the queer servant, long passed the law. Queer servants are often doubly criminal – murderous or thieving – and little has changed with this depiction over time.

Inspired by Powell’s work and the shared experiences of their own relatives lives in service, working-class actors Jean Marsh and Eileen Atkins conceived of an idea which would later become a highly successful television series for London Weekend Television, Upstairs Downstairs (1971-1975). It sought, for the first time, to emancipate the histories of those who served in the glamorous houses that had proven to be a popular subject for television audiences.

Inspired by Powell’s work and the shared experiences of their own relatives lives in service, working-class actors Jean Marsh and Eileen Atkins conceived of an idea which would later become a highly successful television series for London Weekend Television, Upstairs Downstairs (1971-1975). It sought, for the first time, to emancipate the histories of those who served in the glamorous houses that had proven to be a popular subject for television audiences.

Upstairs Downstairs’ foundation lay within family history, and the societal differences between the past and the present. Although domestic servants were shown in recent television drama serials, such as the well received Forsyte Saga (BBC, 1967), they only functioned to serve their employers within the narrative. Once their trays disappeared from well appointed drawing-rooms, audiences were as oblivious to the goings on of their everyday lives as their employers had been. Dominic Sandbrook has suggested that the popularity of the domestic service drama, particularly Upstairs Downstairs, suggested that the ‘middle aged middle classes were unsettled by the uncertainties that had befallen Britain in the 1950’s and 1960’s; they saw an older Britain – something reassuring because it was a hierarchical, organic world where everyone knew their place. They were very reassuring programmes in an age of anxiety’. This interpretation overlooks much of the content of these dramas, which often attempted to portray the social friction between the worlds that existed between floors. Moreover, it certainly ignores the origins of this particular programme, which sought to give voice to the largely unheard working class women and men who had both worked within and fought against this hierarchical way of life. Speaking in 1972, after the equal pay act of 1970, Jean Marsh (co-creator of Upstairs Downstairs) stated in The TV Times that she had wanted to focus chiefly on the history of women in service because ‘…some sort of movement is still necessary. Women aren’t paid equally… I can go out to work, keep myself and keep my parents…I can cook, sew, drive. I am totally self reliant and I can still manage to look like a girl… it is very difficult for any man to accept this.’ Both Atkins and Marsh were interested in giving voice not only to those below stairs (which incidentally was their working title) but also to dramatise the histories of their female ancestors, and to illuminated the culturally forgotten many who had lived and work in domestic service.

Their vision, however, was not realised in its entirety. Scripts were written by a number of authors; some who shared her views on giving voice to the history of women, such as Fay Weldon. However, under the production of John Hawkesworth and John Whitney, drafts would be changed by script editor Alfred Shaughnessy. Peter Wildeblood, famed for his polemical account of his arrest for homosexual offences, penned a script for an episode which was so drastically altered by Shaughnessy that Wildeblood asked for his name to be removed. His plot was totally re-written, and the queer valet morphed into a murderer.

George Innes (Alfred, left) and Christopher Beeny (Edward, right) in Upstairs Downstairs (1973)

Alfred, who appeared in series one and who returned dramatically in series three, is drawn heavily from Powell’s description of the queer valet. He is, for example, older and more ‘feminine’ than the other footmen. Marsh describes that Actor Gorge Innes as brought a ‘…gothic’ presence within the cast and was memorable for his unpredictable and often bitter temperament He is not, however, quite the ‘jelly’ of Powell’s memory, but far more identifiable as a ‘queane’. Another distinction from Powell’s valet is his ‘place’ within the household. He is not popular with the staff, as Powell had suggested her queer Valet was, and is only liked by Rose (played by Marsh) who has romantic feelings for him. It is easy to see why Wildeblood distanced himself from the heavily revised and rather histrionic script. Alfred, who had eloped from the screens in the first series and had gone abroad to work for a German baron, appears soaked and dishevelled at the back door of 165 Eaton Place. Rose, the head house parlourmaid, discovers him and is told by Alfred that, after a broken engagement, he has returned to England and has no place to stay. Rose conceals him from Hudson, the Butler, but the staff soon catch on to ‘Roses’ pigeon’ and Hudson notifies the master. His timing is impeccable, as a detective from Scotland Yard had just arrived to ask some ‘unsavoury’ questions about their former employee. Alfred senses that the walls are closing in on him and grabs the footman Edward, whom he holds at knifepoint, while resisting arrest for the murder of a Lithuanian gentleman with whom he had been in a sexual relationship. The episode ends with Alfred’s hanging for murder. Not the best start (or end) to a characterisation of queer life ‘downstairs’, I grant you, but then things didn’t really get better from there.  Capitalising on the success of LWT’s Upstairs Downstairs, the BBC nabbed John Hawkesworth, its producer, who created the 1976 smash hit The Duchess of Duke Street. Loosely based upon the life of Rosa Lewis, the “Duchess of Jermyn Street”, who ran the Cavendish Hotel in London, Gemma Jones was cast in the title role of Louisa Leyton/Trotter, the eponymous “Duchess” who works her way up from servant to renowned cook to proprietrix of the upper-class Bentinck Hotel in Duke Street, St. James’s, in London.

Capitalising on the success of LWT’s Upstairs Downstairs, the BBC nabbed John Hawkesworth, its producer, who created the 1976 smash hit The Duchess of Duke Street. Loosely based upon the life of Rosa Lewis, the “Duchess of Jermyn Street”, who ran the Cavendish Hotel in London, Gemma Jones was cast in the title role of Louisa Leyton/Trotter, the eponymous “Duchess” who works her way up from servant to renowned cook to proprietrix of the upper-class Bentinck Hotel in Duke Street, St. James’s, in London.

There are a number of queer characters in this production, which centralises around domestic service, and crucially the difficulties and complexities of social mobility in the Edwardian era. Gaspard, a queer Belgian refugee in the second series that focuses on the First World War, was a point of much contention during the two episodes in which he featured. His skills as a patissier marked him as different amongst the staff: an effeminate skill employed during a hyper-masculine wartime environment. His demeanour and ‘feminine’ skills queer him: Merriman: “He flounces and flaps around like a pet poodle” Star: “We know what sort this Belgium bloke is don’t we Mr. Merriman? We had a name for his sort in the Army” Merriman: “He’ll be rolling his hair and putting on scent before long, you mark my words” Mrs. Cochran “I really don’t like to leave him alone with Ethel” Star: “I think she’s quite safe!”

It soon transpires that Gaspard is assisting a German spy, resident in the hotel, and rather than face the noose that hanged Upstairs Downstairs’ Alfred, Gaspard dies alone in his room, after deliberately leaving the gas to his unlit fire on. His suicide confirmed and upheld the narrative so lucidly conveyed in the script: that queers were cowardly, feminine and treacherous.

The BBC did not confine their queers to the downstairs quarters, with characters such as Hugo ‘Saffron’ Walden occupying some of the most exclusive suits of the Bentinck Hotel. Their elevated status didn’t, however, buy more generous characterisations. Saffron is a trouble maker, a blackmailer and above all a gossip. He is tolerated within ‘polite’ society because of his ability to satisfy enough of the codes by which this particular society operated: his social background and the financial stability that it realised ensured that he was ‘part of the club’. Although we understand that everybody in ‘society’ knows that ‘Saffron’ Walden is queer, he maintains a fragile membership within it; one that could be made less secure by the proof of his sexuality. His enjoyment of the gossip that he procures often contained the potential for his ostracism from the society in which it is drawn: Louisa: “Alright you old ratbag, spit it out! Your poison… get it over with, get out of me sight.” Hugo: “Have I stumbled across something I oughtn’t?” Louisa: “Stop your mischief and get out of ‘ere! Now lets get one thing straight, If I find you’ve been telling tales to your dowdy Duchesses, I’ll tell them what you get up to with your loverboys, and that’ll be your meal-ticket gawn, I’m warning yer!”

The Queers in The Duchess of Duke Street were almost indistinct from those of Upstairs Downstairs. Homosexuality was tolerated above stairs, providing it ‘dare not speak its name’, but could be a conveniently employed reason to ostracise queers when they overlooked or challenged other societal norms. Below stairs, queers were treacherous outsiders whose sexualities were a fundamental factor of their lonely, miserable deaths. Both below and above stairs, homosexuality meant an insecure tenure within the social structure of the day. In a reversal of Powell’s queer valet, the homosexuals in these productions are liked by few, because of the scheming characteristics that code them as queer.  It was not until Julian Fellows’ first venture into the writing of domestic service dramas that the more sociable queer appeared. Released in 2001 and directed by Robert Altman, the shooting party at Gosford Park is peppered with queers. Jeremy Northam portrays the only real-life character Ivor Novello, who is the nephew of the fictional lord of the manor. He is part of the society which frequents Gosford Park by birth, but also is alienated from it by membership to an outside club – Hollywood. Hollywood is a firmly threaded outsider to the close-knit fabric of upper class British society, and this disparity between cultures is exemplified by the queer, Jewish film producer, Morris Weissman, who accompanies Novello to Gosford Park. He is universally loathed by all for his inability to understand and comply with the rigidity of social codes.

It was not until Julian Fellows’ first venture into the writing of domestic service dramas that the more sociable queer appeared. Released in 2001 and directed by Robert Altman, the shooting party at Gosford Park is peppered with queers. Jeremy Northam portrays the only real-life character Ivor Novello, who is the nephew of the fictional lord of the manor. He is part of the society which frequents Gosford Park by birth, but also is alienated from it by membership to an outside club – Hollywood. Hollywood is a firmly threaded outsider to the close-knit fabric of upper class British society, and this disparity between cultures is exemplified by the queer, Jewish film producer, Morris Weissman, who accompanies Novello to Gosford Park. He is universally loathed by all for his inability to understand and comply with the rigidity of social codes.

Below stairs, Ryan Phillippe’s character Henry poses as Weissman’s valet. Henry Denton is not quite what he seems, however. Not only is Denton actually an actor, posing as a valet to learn the rules for a film, but his predatory sexual behaviour with women (above and below stairs) is made complex by his sexual relationship with his employer, Weissman. Denton is not a likeable character, but we are never quite sure if he is simply ‘gay for pay’ within the narrative. Nevertheless the inability to conceal his sexual urges similarly others him from both upstairs and downstairs, particularly when his true identity as bed-hopping, foreign actor jeopardises the codes that exist between the floors which he has transcended.

In Jeremy Swift’s footman Arthur, however, we see something of Powell’s queer character. He is soft, demure and desperately in need of love. He is sociable with the majority within the servants quarters, and yet somewhat teased by others for his inability to fulfil his desire to dress Ivor Novello, and in the process catch a glimpse of him in his ‘under britches’.

BBC’s Upstairs Downstairs’ dramatisation of Lady Malcolm’s Servants’ Ball, with queers being ejected

When the BBC revived the old ITV’s Upstairs Downstairs in 2010, a lesbian storyline was deemed by the Daily Mail to be a ‘cheep ploy to boost ratings’, whilst viewers complained to Points of View that it was ‘not the job of the BBC to promote this kind of behaviour’ and vowed to stick with old reruns of the show. When in its second series Lady Malcolm’s Servants Ball was dramatised for the first time on screen, we are given but a glimpse of the queer men who we know attended, as they are ejected from the Albert Hall.

Compared to the safely queer character that Arthur presented in Gosford Park, the character of Thomas Barrow in Julian Fellows’ Downton Abbey seemed at first to revert to the earlier, villainous characterisation realised in Upstairs Downstairs. Few who tolerated Barrow in the first series actually liked him. As an audience we were invited to love to hate the bitter, venomous and sharp-tongued queer footman, who revelled in exposing people to their weaknesses. If a scandal featured in the plot, we knew that Thomas and his partner in crime O’Brien were somehow entangled within its melodramatic web. The list of Thomas’s offences is certainly impressive. In addition to his sexuality, Thomas is shown stealing wine from the cellar, attempting to frame Bates for the crime, attempting to steal Carson the Butler’s wallet, mocking a man for mourning his mothers death, self inflicting a nonfatal ‘Blighty’ wound in order to leave the battlefront, and attempting to navigate the black market of rationed goods. Julian Fellows maintains that these actions were written to explain the difficulties of being queer in the early twentieth century. Barrow’s evil streak is born of the pressures that he faces in his everyday life as a closeted queer man:

“Perfectly normal men and women were risking prison by making a pass at someone. Their whole life was lived in fear, and ruin and humiliation and career after career would be smacked down. I think it’s useful to remind people that many things that they take for granted, are, in terms of our history, comparatively new. But I also felt it was believable that someone living under that pressure would be quite snippy and ungenerous and untrusting. But once you understood what he was up against, you’d forgive quite a lot of that. I like to write characters where you change your mind, without them becoming different people.”

I am not foul Mr. Carson. I may not be the same as you, but I am not foul.

Although it has taken five series for Julian Fellow’s to invite us to ‘change our mind’ about Thomas, it is somewhat depressing that this transformation of character steamed from his determination to chemically change his sexuality. I feel sure, however, that in time-old Downton fashion, this softer, kinder Thomas won’t stick around for long. Culture has not been kind to our queer historical ancestors who spent their lives in service. When queer servants appear on screen, which is frequently, they are often portrayed as ‘doubly criminal’ – their sexuality is illegal, and the illegality of their sexuality in turn makes them ‘vile, twisted creatures’. In many ways they comply with a long history of such portrayals of homosexuality on screen – From the terrifying Mrs Danvers in Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940), to the notorious queer serial killing film Cruising (1980), queerness has been a code for danger, criminality and vice. If we are to discover the realities of queer life in service, we first need to ask ourselves why culture has been so virulently cruel to its memory, and how we can unpick the layers of tarnish that have made opaque the often hidden history of the downstairs queers.

[“Julian Fellows maintains that these actions were written to explain the difficulties of being queer in the early twentieth century. Barrow’s evil streak is born of the pressures that he faces in his everyday life as a closeted queer man.”]

I’ve never heard of anything so ridiculous in my life. I’m almost curious about how Fellows came up with that explanation.